Plato’s Metaphysics and Epistemology

Realm of Being / Realm of

Becoming

The Realm of Being and

“The Forms”

Epistemological

Ramifications of this Metaphysical View

Plato’s Doctrine of Reminiscence

The Traditional Account of Knowledge

Ethical Ramifications

of this Metaphysical View:

Psychological Ramifications

of this Metaphysical View

Aesthetic Ramifications

of this Metaphysical View

Epilog (This is

repetitive. - Skip if you already pretty much understand the foregoing.)

It’s all in Plato, all in Plato: bless me, what do they teach them at those schools!

C.S. Lewis, The Last Battle spoken by Digory Kirke in Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia.

It was said that he was born of a virgin, and that his father was a deity. He was worshipped by some as a god after his death, and he changed the course of Western civilization. No, it's not who you think. I am referring to Plato (429-347 b.c.), about whom all sorts of apocryphal stories grew up almost immediately after his death.

•

Recall that Plato’s teacher.

Socrates, was executed for asking questions and seeking truth/ wisdom.

•

In his search for truth and knowledge,

Socrates ended up exposing frauds and deceivers and moral relativists.

•

Therefore, Philosophy was a (sacred?)

vocation for Plato, in the service of truth, goodness, beauty and the ordered

State.

Philosophy had a political mission for Socrates/ Plato. The great orator, Gorgias (483–375 BCE)[1], says a man well trained in rhetoric gains "the power of ruling his fellow countrymen" because he can "speak and convince the masses."[2] In fact, Gorgias says, there is no subject on which he could not speak before a popular audience more persuasively than any professional. Is rhetoric really that powerful? This speaks to what Plato thought the mission of philosophy was. It was to distinguish appearance from reality.

·

Plato was

both a writer and a teacher.

·

Opened a

school on the outskirts of Athens dedicated to the Socratic search for wisdom.

·

Plato's

school, then known as The Academy, was the first university in western history

and operated from 387 B.C. until A.D. 529, when it was closed by the Roman

Emperor Justinian.

·

His popular

published writings are in the form of dialogues, with Socrates as the principal

speaker. This discussion format has become known as Socratic dialogue.

Realm of Being / Realm of Becoming

Plato attempts to reconcile two prominent

opposing metaphysics of his day:

- Parmenides-

reality (Being) must be eternal and unchanging and therefore is distinct from

the world of our experience.)\

- Heraclitus-

reality is indeed that world of our experience and is constantly changing.

Also, Plato borrows heavily from Pythagoras:

-We have a priori knowledge of objective,

non-physical abstract entities which are constant and unchanging. And these entities structure the world we see

around us.

Note: Plato is a metaphysical dualist. He

denies the monism of his predecessors.

That is, Plato believes that in order to explain reality one must appeal

to two radically different sorts of substances, in this case, material

(visible) substance and immaterial (invisible) substance.

So reality can be seen as divided into

two “realms,” the Realm of Being and Realm of Becoming. Key to understanding Plato’s

Metaphysics is his distinction between these two “realms.”

The Realm of Being

Realm of Immaterial Objects

(Invisible) This is a level of reality

which is timeless and eternal and ultimately regulates the material objects

with which we interact on a daily basis.

Known as "Ideas" gk=“εἶδος”

/ "Eidos"

But what sort of a thing is a

“form?”

First it should be noted that Forms

seem to be precisely the sorts of things that Socrates was looking for when he

engaged in dialogues in Athens (e.g. What is it that unites then many instances

for Justice as one?) To know the essence

of, say, justice, is to know what the nature of justice is, what defines “justice”

and distinguishes it from everything that is not justice. It would seem that to

know what justice is, is to know the very Form of Justice.

•

But what kind of thing exactly

is a “Form” for Plato?

•

What is it that one

knows?

•

And how does one come to

know it?

For instance, is it a kind of physical

object, observable through one or more of the five senses? Is it something subjective, an idea in our

minds, knowable via introspection? Is it something conventional, a mere way of

speaking and acting that we pick up from other members of our community, but

which might change from place to place and time to time?

To the last three questions, Plato

would answer with a very firm “No,” “No,” and “No.”

Let us begin by considering a somewhat

intuitive example of a Form: a triangle.

Actually, let us consider several

triangles:

Consider all these several triangles:

small ones, large ones, very large ones.

Some are some isosceles, some scalene, some obtuse, and so on. Do these many things have some one thing in

common? Are these “many” in any respect “one?”

Is there any sense in which we might

say these “many” are all “the same,” all

“one?” Well, yes; they are

all triangles. That is to say, each is a

closed plane figure with exactly three straight sides. This defines the essence, the nature, or the

FORM of triangles. (i.e. Triangularity).

And it is by virtue of possessing this common Form that they ARE

triangles. So “Triangle”

names a necessary set of properties, not merely an accidental list of

properties, that all triangles share. And

these necessary properties are jointly sufficient. This special combination of properties is

what all and only triangles have in common, by virtue of the possession

of which they ARE triangles.

Now let’s note a couple of

things:

Notice that no particular depiction of

a triangle is going to be perfect. They will necessarily lack, or

at least not perfectly exemplify, features that are part of being a triangle. They are going to have lines that are

partially broken, or corners that are not perfectly closed, or lines that are

not perfectly straight or merely one point thick, no matter how carefully one

draws them. Nevertheless, we recognize them to be

triangles, albeit, imperfect triangles.

Notice further that all of particular depictions

of triangles are going to have some properties that have nothing to do will

being a triangle (like being black or blue, or being equilateral or small). These features are features of some triangles

and not of others. They do not enter

into the essence of triangle. Nothing

about being a triangle requires having these (accidental) features.

So lets take

stock of where we are so far.

- When

we understand triangle form we understand perfect triangle form, this

despite the fact that we have only ever seen imperfect triangle

representations.

- Triangle

representations only approximate triangularity to some limited extent;

they are triangles “more or less.”

- Further

all triangle representations (imperfectly) possess certain necessary

features (i.e. properties essential to being a triangle).

- As

well as a whole host of other properties that have nothing to do with

being a triangle (i.e. properties accidental to being a

triangle).

- Understanding

Triangle Form requires understanding this difference between essential and

accidental properties.

- Recognizing

individual triangles as triangles requires understanding

this difference.

A further note about this triangle

form: it does not change.

•

But all material things, including

material triangle representations, come

into existence and go out of existence and change in other ways as well.

•

Yet, the essence of triangularity stays

the same.

So “Form of Triangle ” does

not name a physical object. All physical

objects are particular, visible changing material things. Forms, by contrast, have none of these

properties.

So Forms are NOT Physical Objects

Thus, Plato concludes two related, but

independent things from this:

1. When we grasp the essence or nature

of a triangle, what we grasp is not something material or physical. Forms then are NOT physical objects.

(Metaphysical claim about Forms)

2. When we grasp the essence or nature

of a triangle, what we grasp is NOT something we grasp nor could we grasp

through the senses. (Epistemological claim about our knowledge of Forms)

Is Triangle Form a Subjective Construct or Cultural

Artifact?

No.

We know many things about triangles

-not only their essential features, but also we know things that follow from

that essential nature, such as the fact that their interior angles necessarily

add up to 180 degrees, that the Pythagorean theorem is true of right triangles,

and so forth. These things are true

quite apart from our knowledge of them; they were true long before the first

geometer drew his first triangle in the sand, and will remain true even if

every particular material triangle were erased tomorrow.

What we know about triangles are

objective facts, things we have discovered rather than invented. It is not up

to us to legislate or construct that the interior angles of a triangle should

add up to 180 or that the Pythagorean Theorem should be true. We

could not individually or collectively construct these facts away. Long before we discovered these facts, they

were true and will remain true long after we're all dead.

What we know when we know the essence

of triangularity is:

- something

universal rather than particular

- something

immaterial rather than material

- something

timeless rather than ephemeral

- something

we know through the intellect rather than the senses

Now if the essence of triangularity is

something that exists neither as an object in the material world nor merely as

an object in the mind of a human or the collective of humans, then it must have

a unique kind of existence all its own, that of an abstract object existing in

what Platonists sometimes refer to as “The Realm of Being."

But Plato does not restrict himself to

geometric forms. There are other Forms in the Realm of

Being. What is true of triangles, in this regard, is

also true of physical objects such as cats.

Were I to show you two cats:

|

|

|

and ask “Is there something that

these two objects have in common?” you would likely say, “Yes,

there is.”

But note that, on the face of it at

least, you are making an existential claim.

You are claiming that “There IS something.” or rather,

“There exists some ‘thing’ that they have in common.” And what is that thing? What do the two cats have in common?

Cat Form.

Alternatively, one might ask:

“What

is it that all on only cats have in common in virtue of the possession of which

they ARE

cats?”

Likewise, one might ask:

“What

is it that all on only good things have in common in virtue of the possession

of which they ARE good?”

The answer to these questions are:

“The Form of Cat” and “The Form of the Good”

respectively.

·

But, these forms are not constructions

of human thought. (Platonic Realism is

opposed to Nominalism[3])

*Note: you must not imagine that the abstract ideas which we come

to understand through reason are somehow “created” by reason.

The Pythagorean Theorem was true long before anyone knew it. Just actions

are just (embody the Form of Justice) whether anyone understands them to be

just or not.

The Forms are:

·

like perfect examples or blueprints,

definitions of particular realities.

·

that which "all and only things of

a kind have in common and are what they are in virtue of possessing

that.”

Residents of the Realm of Being

Include-

Forms of:

Geometry

Abstract

“Ideas*” (e.g. Truth, Justice, Goodness, Beauty)

Essences

or “Natural Kinds” (Dogs, Trees, etc.)

We can recognize cats as

cats only because we know (can recognize) the form of cat. Say I show you three cats:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Then I show you a new object and asked

you, “What is it?”

You would be certainly correct to say

that you have never seen that before in your life. You indeed have never seen this

particular before.[4] But if you recognize it as something you have

encountered before; it is only because you mind understands “cat

form.”

You would likely recognize it as

something you have encountered before.

“It’s a cat.” you would say. But you could only come to the correct

judgement if you were recognizing something with which you were already

familiar, because your mind understands “cat form.” According to Plato, this thing that you

recognize is NOT identical to anything you have ever seen before with your

eyes. As with triangles, no actual cat

is perfectly a cat, embodying cat form perfectly. Individual cats are just cats… more or

less. And, as with triangles, any

particular cat will have accidental properties that have nothing to do with

being a cat. Every cat that you have

ever seen has either had green eyes or blue eyes or yellow eyes, etc.. Each has

been fat or skinny or fluffy or hairless.

But Cat Form has none of these qualities.

*Note: this is part of what Plato means by calling Forms invisible. These are “invisible” meaning you

have never seen any of them nor could you. Nor can you “image” them in your

mind. They are known to you only via

your intellect. This leads Plato to say,

“What we think we cannot see and what we see we cannot think.”[5]

Individual cats are cats (and not, say,

dogs) because they exhibit “cat form” (and not dog form). Were there no such thing as cat form, there

could not be any cats at all. That means

that:

- The

sheer existence of cats is sufficient to assure us that there must be Cat

Form.

- Cat

Form governs or orders the natural, visible world.

- Cat

Form is ontologically prior to (and therefore more real than) individual

cats. Particulars are ontologically

dependent on the form in a way similar to the way reflections of dependent

upon the objects of which they are a reflections, or shadows are dependent

upon the objects that cast them,

- If,

somehow, we were to get rid of all cats (Perish the thought.) Cat Form

would be no more affected than the Pythagorean Theorem would be affected

by erasing right triangles.

Thus, forms are the “most real,”

most lasting, most permanent aspect of reality.

They regulate the world of appearances. Particular instantiations,

by contrast, can hardly be said to be “real” at all. Further, the only reason particulars are the

particulars that they are is in virtue of embodying the form they do. The

very existence of particular things is itself parasitic on (thus less real

then) the Forms. The relationship of Forms to their particular instantiations

is similar to that between me and my shadow, or me and a photograph of me. I’m more “real” than they

because they depend on me in a way that I do NOT depend on them.

Note: Any particular courageous act DEPENDS on there being such a

thing as “courage” or “FORM of courage.” Thus,

according to Plato, the forms are metaphysically prior to the particulars.

Thus, Ultimate Reality (The Forms) is

“reflected in/ shadowed by” the constantly changing (less perfect)

world of our experience. Plato refers to this latter level of reality as "The

Realm of Becoming" The Forms are

themselves arranged into a hierarchy, the arch form being the Form of the

Good.

·

The Realm of Material Objects

(The Visible)

·

The Level of reality which we

experience through our senses

Residents of the Realm of Becoming

Include:

Particular

things, (e.g. actual dogs, trees, houses)

Triangle

Representations

Particular

Good Things

Particular

True Statements/ Utterances

Particular

Just Acts

Particular

Beautiful Objects

All of these endure only for a time and

then pass away.

The Many can indeed be One

Socrates, Aristotle, and President Joe Beden,

though distinct and separated by time and space, are all men because they all

participate in the same one Form of Man. Fido, Rover, and Spot are all dogs because

they all participate in the Form of Dog. Paying your phone bill, staying faithful to

your spouse, and defending an innocent child are all just actions because they

participate in the Form of Justice.

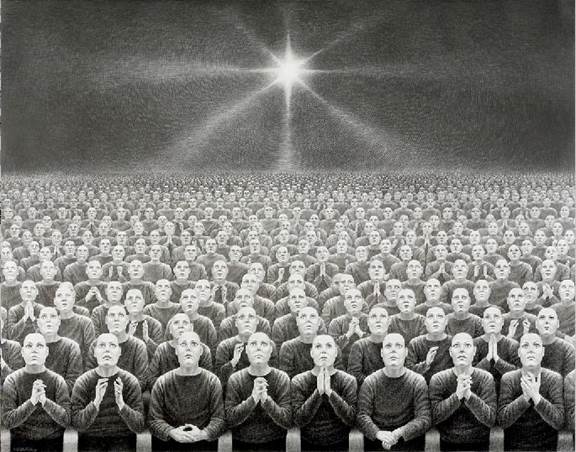

Plato realizes that most humans are

never really aware of this realm of Forms and it’s relation to the

visible world. Regrettably, according to

Plato, they are deceived and take appearance for reality. They believe the things that they see before

them to be what is real when in fact it is merely an imperfect reflection of

what is REALLY real. To illustrate this

point, Plato offers his famous “Allegory of the Cave.”

In order to understand Plato's theory,

we have to entertain the notion that not everything that is real exists in

space and time. Indeed, the whole point

of his Theory of Forms is that, if true, it proves that there must be a

transcendent immaterial dimension to reality.

This view, though ancient, is also contemporary. For instance see Nobel Laureate mathematical physicist

Roger Penrose and the (p)latonic Objectivity of

Mathematical Realities.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ujvS2K06dg4

Plato offered an allegory the help illustrate

what he thinks is going on here.

The Allegory of the Cave

Is not the dreamer,

sleeping or waking, one who likens dissimilar things, who puts the copy in

place of the real object?[6]

- Plato

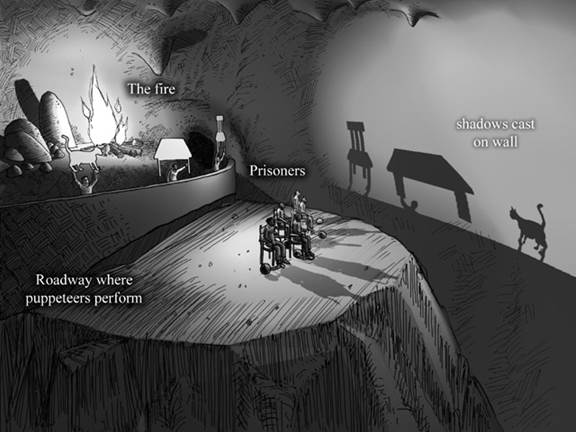

[Socrates:] … let me show in a figure how far our

nature is enlightened or unenlightened: --Behold! human beings living in a

underground den, which has a mouth open towards the light and reaching all

along the den; here they have been from their childhood, and have their legs

and necks chained so that they cannot move, and can only see before them, being

prevented by the chains from turning round their heads. Above and behind them a

fire is blazing at a distance, and between the fire and the prisoners there is

a raised way; and you will see, if you look, a low wall built along the way,

like the screen which marionette players have in front of them, over which they

show the puppets.

[Glaucon:] I see.

And do you see, I said, men passing along the wall carrying all

sorts of vessels, and statues and figures of animals made of wood and stone and

various materials, which appear over the wall? Some of them are talking, others

silent.

[Glaucon:] You have shown me a strange image, and they are

strange prisoners.

Like ourselves, I replied; and they see only their own shadows,

or the shadows of one another, which the fire throws on the opposite wall of

the cave?

[Glaucon:] True, how could they see anything but the

shadows if they were never allowed to move their heads?

And of the objects which are being carried in like manner they

would only see the shadows?

[Glaucon:] Yes, he said.

And if they were able to converse with one another, would they

not suppose that they were naming what was actually before them?

…

[Glaucon:] No question, he replied.

To them, I said, the truth would be literally nothing but the

shadows of the images.

[Glaucon:] That is certain.

In The Allegory of the Cave, Plato

likens people untutored in the Theory of Forms to prisoners chained in a cave,

unable to turn their heads. All they can see is the wall of the cave. Behind

them burns a fire. Between the fire and the prisoners there is a parapet,

along which puppeteers can walk. The puppeteers, who are behind the prisoners,

hold up puppets that cast shadows on the wall of the cave. The prisoners are

unable to see these puppets, the real objects that pass behind them. What the

prisoners see and hear are shadows and echoes cast by objects that they do not

see.

Such prisoners would mistake appearance

for reality. They would think the things they see on the wall (the shadows)

were real; they would know nothing of the real causes of the shadows.

So when the prisoners talk, what are

they talking about? If an object (a book, let us say) is carried past behind

them, and it casts a shadow on the wall, and a prisoner says “I see a

book,” what is he talking about? He thinks he is talking about a book,

but he is really talking about a shadow. But he uses the word

“book.” What does that refer to?

Plato’s answer was:

“And if they could

talk to one another, don’t you think they’d suppose that the names

they used applied to the things they see passing before them?”

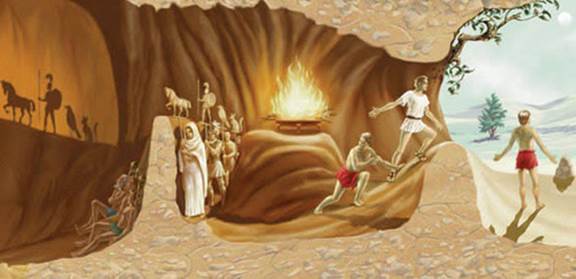

Socrates:] And now look

again, and see what will naturally follow if the prisoners are released and

disabused of their error. At first, when any of them is liberated and compelled

suddenly to stand up and turn his neck round and walk and look towards the

light, he will suffer sharp pains; the glare will distress him, and he will be

unable to see the realities of which in his former state he had seen the

shadows; and then conceive some one saying to him,

that what he saw before was an illusion, but that now, when he is approaching

nearer to being and his eye is turned towards more real existence, he has a

clearer vision, -what will be his reply? And you may further imagine that his

instructor is pointing to the objects as they pass and requiring him to name

them, -- will he not be perplexed? Will he not fancy that the shadows which he

formerly saw are truer than the objects which are now shown to him?

[Glaucon:] Far truer.

[Socrates:] And if he is

compelled to look straight at the light, will he not have a pain in his eyes

which will make him turn away to take and take in the objects of vision which

he can see, and which he will conceive to be in reality clearer than the things

which are now being shown to him?

[Glaucon:] True, he

said.

[Socrates:] And suppose

once more, that he is reluctantly dragged up a steep and rugged ascent, and

held fast until he 's forced into the presence of the

sun himself, is he not likely to be pained and irritated? When he approaches

the light his eyes will be dazzled, and he will not be able to see anything at

all of what are now called realities.

Plato says that we are like those men

sitting in the cave: we think we understand the real world, but because we are

trapped in our bodies, we can see only the shadows on the wall. One of his goals is to help us understand the

real world better, by finding ways to predict or understand the real world even

without being able to see it.

Now, Socrates asks us to imagine what

would happen if the freed enlightened prisoner were to return to the cave and

tell is former prisoners of his adventures and of the true nature of reality

and the distinction between reality and the mere appearances of reality.

And if there were a contest, and he had to compete in measuring

the shadows with the prisoners who had never moved out of the den, while his

sight was still weak, and before his eyes had become steady (and the time which

would be needed to acquire this new habit of sight might be very considerable)

would he not be ridiculous?

Men would say of him that up he went and down he came without

his eyes; and that it was better not even to think of ascending; and if any one

tried to loose another and lead him up to the light,

let them only catch the offender, and they would put him to death.[7]

We can come to grasp the true Forms

with our minds.

[Socrates:] This entire

allegory, I said, you may now append, dear Glaucon, to the previous argument;

the prison-house is the world of sight, the light of the fire is the sun, and

you will not misapprehend me if you interpret the journey upwards to be the

ascent of the soul into the intellectual world ….

But, whether true or false, my opinion is that in the world of

knowledge the idea of good appears last of all, and is seen only with an

effort; and, when seen, is also inferred to be the universal author of all

things beautiful and right… and the immediate source of reason and truth

in the intellectual; and that this is the power upon which he who would act

rationally, either in public or private life must have his eye fixed. ….

Whereas, our argument shows that the power and capacity of

learning exists in the soul already; and that just as the eye was unable to

turn from darkness to light without the whole body, so too the instrument of

knowledge can only by the movement of the whole soul be turned from the world

of becoming into that of being, and learn by degrees to endure the sight of

being, and of the brightest and best of being, or in other words, of the good.

The Allegory presents, in brief form,

most of Plato's major philosophical assumptions: his belief that the world

revealed by our senses is not the real world but only a poor copy of it, and

that the real world can only be apprehended intellectually; his idea that

knowledge cannot be transferred from teacher to student, but rather that

education consists in directing students’ minds toward what is real and

important and allowing them to apprehend it for themselves; his faith that the

universe ultimately is good; his conviction that enlightened individuals have

an obligation to the rest of society, and that a good society must be one in

which the truly wise (the Philosopher-King) are the rulers.

For Plato the only and proper response

to the Forms (once rightly appreciated) is love. (Philo Sophia) This he expresses well in the Symposium

when speaking about the Form of Beauty (which is the only REAL beauty). Indeed the Forms are the ONLY things to be

truly loved.

You see, the man who has been thus far guided in matters of Love,

who has beheld beautiful things in the right order and correctly, is coming now

to the goal of Loving: All of a sudden he will catch sight of something

wonderfully beautiful in its nature; that, Socrates, is the reason for all his

earlier labors: First, [Beauty] always is, and neither comes to be nor passes

away, neither waxes nor wanes. Second, it is not beautiful this way and ugly

that way, nor beautiful at one time and ugly at another; nor beautiful in

relation to one thing and ugly in relation to another; nor is it beautiful here

but ugly there, as it would be if it were beautiful for some people and ugly

for others. Nor will the beautiful appear to him in the guise of a face or

hands or anything else that belongs to the body. It will not appear to him as

one idea or one kind of knowledge. It is not anywhere in another thing, as in

an animal, or in earth, or in heaven, or in anything else, but itself by itself

with itself. It is always one in form;

and all the other beautiful things share in that, in such a way that when those

others come to be or pass away, this does not become the least bit smaller or greater

nor suffer any change.[8][9]

Full text at:

http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/platoscave.html

Or

http://www.historyguide.org/intellect/allegory.html

So did Plato anticipate cinema? Where we in caves an mistake shadows for

reality?

Epistemological

Ramifications of this Metaphysical View:

Since Forms are not perceived (empirically),

they cannot be learned through experience; we never experience forms

(sensuously). We have never seen, nor could we ever see a triangle.

Yet we do know them and lucky for us we do since the laws of geometry govern

the world. (Just try to build a deck on the back of your house without

it.) Cat Form determines how cats

behave. The knowledge of Cat Form is

what allows us to recognize cats when we see them, predict their behavior, etc. This is, after all, what one studies in veterinary

school.

So, if we don’t learn the forms

through experience how DO we acquire

knowledge of the Forms? Plato reasons

that we must have acquired the knowledge of the Forms somehow sometime before

being born (since it was no time after). Otherwise we would never recognize the

truth when we see it.

In the Platonic dialogue The Meno Socrates

“teaches” a slave boy geometry by merely asking him questions. This is supposed to illustrate that the boy

knew the answers already; he merely needed to be asked the right questions in

order to remember. This is the thinking

behind the “Socratic Method” teaching.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DEF035uNC2M

Plato’s

Doctrine of Reminiscence:

All knowledge of the forms must be

gained in some sort of existence before our life on earth begins. Humans attain knowledge of the true forms or

essences of the material world.

This knowledge can be accessed after

birth with the mental processes of recollection or reminiscence that is

stimulated by being reminded.

Plato posited that our minds/ psyches

must predate our bodies because this is the only way a human could gain

knowledge of certain concepts like perfect equality, etc. which cannot be

gained from sensory experience. This is one

of his arguments to establish the existence of an immaterial human soul.

Paradox of Knowledge: Either pursuing truth is futile or unnecessary.

Either we don’t know what the truth is, and therefore can never recognize

it, even when we see it, or we already know it and therefore there is no need

to look.

Plato’s Solution: We know it but forgot. The world around us and good

teachers serve to jog our memory.

Is Plato’s solution too “spooky?”

“To some, the conception

of a previous life with its opportunity for a glimpse of the eternal essences

may appear fantastic. Yet to any one who believes

that the soul survives the body the view that the soul antecedes the body

should not seem unreasonable. In any case, the transcendental theory is only an

interpretation of the immediate fact that experience fails to account for all

of knowledge. The doctrine of the limitation of empiricism remains, whatever

one's view about the origin of abstract ideas may be. We cannot derive our

categories -- thinghood, quality, relation, causality, -- from experience,

because we use them in understanding experience; we cannot derive our laws of

thought -- such as the law of contradiction -- from experience, because they

are presupposed in any actual process of thinking; we cannot derive universal

principles from experience, because experience is limited to particular cases;

finally, we cannot derive any concepts (such as white-square) from experience,

because they constitute standards by which the data of experience are measured.

The kernel of the Platonic theory is rationalism, namely that there is a

non-empirical element in knowledge.” [10]

Therefore:

Plato believes that our Consciousness

(Soul/ Mind/ Psyche) predates our bodies and will, in all likelihood, postdate

our bodies as well. We (our souls) are immortal- like the forms

themselves. The individual is identified

with his or her MIND, and NOT his or her body. All real knowledge is a matter of remembering

the forms. Truth must be in us, innately. Thus Plato defends the claim that we have

“innate ideas.” Indeed, his

is perhaps the most robust notion of innate ideas.

Innate Ideas: knowledge and ideas already gained by the time of our

birth.

Experience is useful only in so far as

it jogs our memory of the forms. But it does not/ cannot give us any real

knowledge of Ultimate Reality. (This makes him a Rationalist)

Note: A Rationalist

is one who believes that the senses are a poor or unreliable source of

knowledge and the true knowledge comes from introspection and there exists

innate ideas. (This is contrasted with Empiricists

who take exactly the opposite positions to those of the Rationalist.)

Note:

Even further, he is a mystic- Real/ Ultimate knowledge is imparted to

humans by means of a supernatural extraordinary experience. (Thus he has an affinity

with certain religious traditions.)

In the Theaetetus Plato suggests the inquiry should be directed at trying

"… to find a single formula that applies to the many kinds of

knowledge" (148d). Plato presumes

that there is a single thing, a common form of knowledge, which should be

capable of being defined.

Plato rejected the notion that

knowledge is simply “true belief.” A jury may correctly believe

that the accused is guilty, but if their belief is based on hearsay, we would

say that they have true belief, but not knowledge. "But if true belief and knowledge were

the same thing, the best of jurymen could never have a correct belief without

knowledge. It now appears that they must be two different things" (Theaetetus

201c). In the Meno, Plato explores further the relation between knowledge and

true belief (which is there called "opinion").

However, Plato probably would not have

claimed the jury could ever have knowledge in the truest sense. In The

Republic, Plato claims that sensible objects and events (like the

commission of a crime) are stuck at the level of true opinion for metaphysical

reasons. For Plato, the only kind of knowledge fully worthy of the title

“Knowledge” would be knowledge which is certain, timeless and

necessary. True reality lies if the

realm of forms alone and thus true knowledge resides in knowledge of the forms

alone. Since the realm of becoming is a

shadow-image of the true reality, genuine

knowledge in the truest sense of the world of appearances is metaphysically

impossible. All that we can ever aspire

to would be approximate knowledge.

"When

[the soul] inclines to that region which is mingled with darkness, the world of

becoming and passing away, it opines only (i.e.

true opinion) and its edge is blunted, and it shifts its opinions

hither and thither, and again seems as if it lacked reason."[11]

In the Republic, Book VI, 507C,[12]

Plato describes two classes of things, those that can be seen but not thought, and those that can be thought but not seen. In the

visible world, shadows, reflections, as well as this things of which they are

shadows and reflections (plants, animals, etc.) are illuminated by the sun and

“known” to us by sight. But

of the invisible world, mathematical equations and proofs, as well as the forms

themselves, are illuminated by the Form of the Good and known to us (in the

fullest sense of knowledge) by intellect. As there are two metaphysically

distinct types on objects, owing to the metaphysical nature of these objects,

there are two types on “knowing” each directed to its object. There modes of “knowing” are

unequal, the former rising as most to “true opinion” the latter

only fully deserving of the title “knowledge.”

![]()

|

|

A |

B |

C |

D |

|

509D-510A |

Likenesses, images, shadows,

imitations, our vision (ὄψις, ὁμοιωθὲν) |

The physical things that we

see/perceive with our senses (ὁρώμενα,

ὁμοιωθὲν) |

Opinion, beliefs (δόξα,

νοῦν) |

Knowledge (γνῶσις,

νοούμενα) |

|

511D-E |

Conjectures, images, (εἰκασία) |

Trust, confidence, belief (πίστις) |

Understanding, hypothesis (διανόια) |

Intellection, the objects of reason (νόησις, ἰδέαι,

ἐπιστήμην) |

“This,

then, you must understand that I meant by the offspring of the good which the

good begot to stand in a proportion with itself: as the good is in the

intelligible region to reason [CD] and the objects of reason [DB], so is this

(sc. the sun) in the visible world to vision [AB] and the objects of vision

[BC].” [13]

|

Type of cognition |

Type of object |

|

Philosophical understanding |

Ideas

(Forms),

especially the Idea

(Form) of the Good |

|

Mathematical reasoning, including theoretical

science |

Abstract

mathematical objects, such as numbers and lines |

|

Beliefs about physical things, including empirical

science |

Physical

objects |

|

Opinions, illusions |

"Shadows"

and "reflections" of physical objects |

So again, we cannot see what we can think,

and we cannot think what we see. The

fundamental problem with the world of the senses is just that it is grasped by

the senses, not by reason. Plato (in places) seems to allow that “true

opinion” could become knowledge if it was “tied down” with

"an account of the reason why."

This later is widely accepted among philosophers as “The

Traditional Account of Knowledge.”

The Traditional

Account of Knowledge

Knowledge is True, Justified Belief.

•

Knowledge =

–

True

–

Justified

–

Belief

•

Kn = TJB

From the time of Plato on this view of

knowledge as true justified belief became the standard accepted by western

philosophers largely up until the 20th century. As a result western

epistemology has largely been concerned with the question of what constitutes

justification and what is the nature of truth. Interestingly however in the

20th century the traditional account of knowledge has come to be questioned and

rejected by many philosophers. For more

information on this contemporary development and epistemology see Edmund Gettier’s

1963 article in Analysis, "Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?"

But ultimate knowledge (for Plato that

which is truly worthy of the name knowledge) will always be lodged in the world

of the intellect/ reason. There is

always room for error in the application of the reason to an empirical issue at

hand. Only when the reason/ forms/ logos itself is the object do we have

knowledge, do we have something that is worthy of the title knowledge. Knowledge of (this) reality is never

changing: gained only through thinking. 2+2 =4 : facts are eternal and

necessary.

Education is best served by asking the

student questions and allowing the student "see" the truth on one's

own (Socratic Method). Real

knowledge is conceptual and verbalize-able.

That which does not yield words or cannot be expressed in words does not

merit the title “knowledge” or wisdom or intelligence.[14]

Philosophical/ Dialectical Project:

The successful conclusion of a

philosophical argument will yield the correct definition of the concept under

discussion, the intellectual articulation and apprehension of the FORM. (E.g.

What it is that all and only courageous acts have in common by virtue of which

they ARE courageous acts.)

Ethical

Ramifications of this Metaphysical View:

The attainment of knowledge of eternal

forms is the only worthwhile activity for humans.

What is most real and lasting and

important about reality (of value, worthy of attention and service) is the

immaterial realm. The most noble part of

ourselves (our intellect-soul) is satisfied by nothing less than the

transcendent forms. Further, what is

most real and lasting and important about an individual (of value, worthy of

attention and service) is the immaterial aspect- the psyche or immortal

soul. It is the only thing about you that could possibly survive the

death of the physical body.

This sentiment would resonate well with

later Christians who taught:

"So

we fix our eyes not on what is seen, but on what is unseen, since what is seen

is temporary, but what is unseen is eternal." 2 Corinthians 4:18

"Do

not store up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy,

and where thieves break in and steal. But store up for yourselves treasures in

heaven, where moth and rust do not destroy, and where thieves do not break in

and steal. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.” Matthew

6:19-21/NIV

“Do

not work for food that perishes but for the food that endures for eternal life,

which the Son of Man will give you.” John 6:27

One of Plato’s ethical slogans: “It

is better to suffer an injustice (which does not jeopardize the welfare of one’s

immortal soul) than to do an injustice (which does jeopardize the welfare of

one’s immortal soul).”[15] To pursue wealth, physical pleasure, worldly

glory for their ephemeral charms is to be metaphysically misguided. The wise

man (philosopher) realizes that these are not to be sought to the detriment of

one’s soul.

(Some)

Psychological Ramifications of this Metaphysical View:

Plato

starting point for his divisions of the psych/soul is the different classes he

observed in society. He concluded that

these natural separations must arise from the psychology of the individuals who

make up society. Plato notes what

motivates people. The objects of our desires

distinguish important differences among these desires.

1) Some desires are directed at

things.

2) Others are directed at reputation

and honor

3) Others are directed at truth.

These

correspond to three distinct part of the soul:

(1) the appetitive (2) the spirited/competitive and (3) the rational.

Plato

explains this tripartite division by an allegory - a charioteer driving two

horses. The charioteer represents the rational part of the soul (3). The black

horse represents the appetitive part of the soul (1) and the white horse

represents the spirited/competitive part of the soul (2).

Plato’s Tripartite Soul

|

Parts of the Soul |

Appetitive (1) |

Spirited (2) |

Rational (3) |

|

Chariot Part |

Black horse on the Left |

White horse on the Right |

Charioteer |

|

Loves |

Emotion, Pleasure, Money, Comfort,

Physical Satisfaction |

Honor and Victory |

Truth, Wisdom and Analyzing |

|

Desires |

Basic Instincts – Hunger,

Thirst, Warmth, Sex…etc. |

Self-Preservation |

Truth |

|

The Virtue |

Temperance |

Courage |

Wisdom |

|

The Vice |

Gluttony, Lust and Greed |

Anger and Envy |

Pride and Sloth |

|

Body Symbol |

Belly/Genitals |

Heart |

Head |

|

Class in od People in Republic |

Merchants/Workers (Make things/

produce/ Self-interested) |

Auxiliaries/Soldiers (Police and

Defend) |

Guardians/ The Philosopher King (Govern) |

|

Star Trek Character (TOS) |

Bones |

Captain Kirk |

Spock |

Mental Health

then was achieved and maintained when reason was in control of the other two

motivators. The city-state was well when

reason was in control of the other two as well.

The city was simply a macrocosm of the individual.

(Some) Psychological Ramifications of

this Metaphysical View:

•

In

Plato’s Republic, people who are dominated by reason will become

philosophers and eventually rulers.

•

People

dominated by spirit will become warriors.

•

People

dominated by appetite will become merchants or manufacturers or workers or

farmers.

•

Reason should

control the soul of the human individual.

•

Rational

people should control the republic.

•

In The

Republic, bright women are given a first-class education and are allowed to

ascend to the level of philosopher-kings.

(Some) Aesthetic Ramifications of this Metaphysical View: (Beauty)

When we recognize that something is beautiful,

we do so because we recognize that it participates in the eternal form of

beauty. Beauty names a transcendent object which does not exist in the world of

sense objects, but of which beautiful objects are mere imperfect copies.[16]

Further, since whether an object participates in the form of beauty or not is

an objective relation with no logically necessary consequences for perception,

it follows that judgements about whether an object is beautiful or not are not

mere subjective reports, but rather claims about objective states or

affairs. They cannot be based solely on sensual appeal and are subject to

revision and correction.

Judgements of

beauty cannot be based solely on sensual appeal and are subject to revision and

correction. Nevertheless,

“recognizing” beauty, like recognizing truth seems to be a

phenomenological revelation or epiphany, an Intuition- a non-evidentially

grounded certainty of an objective truth.

Consider:

All A is B

All B is C

Therefore?

Well…

All A is C

… but

how do you know? (Logical Intuition)

There is felt

similarity between that and the judgement that "X is beautiful."

or "X is more beautiful than

Y."

…but

how do you know?

(Some)

Aesthetic Ramifications of this Metaphysical View: (Art)

If art is merely an imitation of nature

(as Plato thought it was -Mimetic Theory of Art), then art is an imitation of

an imitation. This makes it VERY LOW on the metaphysical ladder. Since art

primarily appeals to our senses and not our reason this makes it VERY LOW on

the epistemological ladder.[17]

Since art directs our attention to the physical qualities of things, and the

physical in general, it is ethically dangerous. Since art appeals to our

irrational emotions, prompting us, sometimes, to weep at playacting and the

like, it is psychologically dangerous.

The wise person regulates the art that

he or she allows into his or her life according to the directives of reason. The wise polis (city-state, community)

regulates the art that it allows into the lives of its citizenry (censorship of

art).

“there

is an ancient quarrel between philosophy and poetry; of which there are many

proofs, such as the saying of 'the yelping hound howling at her lord,' or of

one 'mighty in the vain talk of fools,' and 'the mob of sages circumventing

Zeus,' and the 'subtle thinkers who are beggars after all'

…

Notwithstanding this, let us assure our sweet friend and the sister arts of

imitation that if she will only prove her title to exist in a well-ordered

State we shall be delighted to receive her --we are very conscious of her

charms; but we may not on that account betray the truth.

If her

defense fails, then, my dear friend, like other persons who are enamoured of something, but put a restraint upon themselves

when they think their desires are opposed to their interests, so too must we

after the manner of lovers give her up, though not without a struggle.[18]

Epilog

(This is repetitive. - Skip if you already pretty much understand the

foregoing.)

In speaking with one of your classmates

earlier today I was trying to make the point that Plato's view of how we come

to know forms is very different from what we might call the “common sense”

view many hold today. Whereas today we might commonly say we see a cat then we

see another, cat then we see another cat, and so on, and then we create the

concept of “cat” from our experiences.[19]

Plato, by contrast, thinks that model is entirely backwards.

In fact, to see a cat as a

cat (as appose to an absolute individual particular, unrelated to any

other particular of you have previously experienced) requires that we begin

with the concept of cat form. Thus, we

cannot derive the cat form/ concept of cat form from our

experience. Our experience presupposes

it. Note that, if we perceive each

individual as an individual then they have no common form. Indeed, they have no determination whatsoever.

As individuals they are

undifferentiated.

What differentiates one

individual and thus what serves to make it intelligible and

“thinkable” are those forms (definitive natures) it exhibits. These serve to distinguish it from some and

liken it to others. We cannot know the

individual particular as a particular, but only as the instantiation of some

concept/ form or forms.

So note, if I showed you a cat and then

another cat and then another cat and then showed you a fourth cat that you've

never seen before and asked what you had what this new particular was, you would be quite correct to respond,

“I have no idea; I have never seen that before.” As an individual you have never seen this

individual particular before. What you have known before is cat form, so to see

is as a cat you would need to understand it as an instantiation of cat

form. But how did you know what to see as

relevant similarities with previously seen cats (essential properties) and what

to discard as irrelevant differences (accidental properties)? You could not know which similarities to see as

relevant and which differences to disregard as irrelevant if you did not

already possess the notion of cat form.

Thus you could never come to see these particulars as you could not come to see these as “the

same.”

All this to say that, without knowing

what cat form is, you could never see cats as cats. All you would see is a series of unrelated individual

particulars. Further these particulars would have no intelligible

determinations. They would be undifferentiated being or undifferentiated

particular existence. Certainly this is not knowledge, and this would not allow

us to navigate the world. The mystery to be solved is “Where did our

knowledge of cat form come from?”

Of course, Plato tells his spooky story

about innate ideas. This is a story that

Aristotle rejects in favor of something he takes to be more common sensible. But as we shall see, he has in my view as hard,

if not a harder time explaining how this knowledge of forms arises in our

understanding.